There is also an English version (at the end).

Władysław Teodor Benda, „Archiwum Emigracji”, Toruń, z. 1, t. 10/2009, s. 168-172.

Utalentowany. Pomysłowy. Świadomy tradycji i korzeni. Tytan pracy. Dziecko swego czasu. Ilustrator, malarz, światowej sławy twórca masek. Władysław Teodor Benda, Amerykanin polskiego pochodzenia, jeden z najznamienitszych artystów w Stanach Zjednoczonych[1].

Ojciec – Szymon Benda, wykształcony w Wiedniu pianista i kompozytor, pochodził z Krakowa. Był przyrodnim bratem aktorki teatralnej Heleny Modrzejewskiej. Ożenił się z córką poznańskiego kupca – Xsawerą Sikorską –i miał z nią trójkę dzieci. Najstarszy syn – Władysław Teodor urodził się w Poznaniu, w 1873 r. Choć Szymon imał się różnych zajęć; pracował jako nauczyciel muzyki, kapelmistrz w teatrze, przedstawiciel fabryki fortepianów; rodzina Bendów cierpiała niedostatek. Ciągłe przemieszczanie się z miasta do miasta (Kraków, Poznań, Wiedeń, Tarnów) nie poprawiało sytuacji materialnej.

Dzięki pomocy babki i ciotki Władysław rozpoczął studia artystyczne na Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie. Uczył się pod kierunkiem Władysława Łuszczkiewicza, Izydora Jabłońskiego i Floriana S. Cynka[2]. Od 1894 r. przebywał z Wiedniu, gdzie kontynuował naukę w Szkole Sztuk Pięknych Heinricha Strehblowa[3].

W 1898 r., na zaproszenie siostry, rodzina Szymona Bendy wyjechała do Stanów Zjednoczonych. Modrzejewska stała wówczas na progu wielkiej i dobrze zaplanowanej kariery. Posiadała już dużą posiadłość w Kalifornii oraz rozległe i znaczące znajomości. Ciotka ułatwiła bratankowi wstąpienie w świat artystyczny zlecając zaprojektowanie dekoracji i opracowanie kostiumów scenicznych do „Antoniusza i Kleopatry” wg. Williama Shakespeare’a. Premiera przedstawienia odbyła się 19 września 1898 r. w Baldwin Theatre w San Francisco. Sztuka okrzyknięta została „historycznym wydarzeniem” w dziejach miasta, a kostiumy zdobyły miano „cudownych”[4]. Modrzejewska, występująca w roli Kleopatry odniosła wielki sukces. „Szekspir, jak zwykle, okazał się moim niezawodnym sprzymierzeńcem. Sztuka miała wielkie powodzenie…” – pisała we wspomnieniach aktorka[5].

W 1899 r. zmarł ojciec artysty. On sam przeniósł się do Los Angeles, a później do San Francisco, gdzie studiował w Hopkins Institute of Art[6]. Podróżował także po Europie i Bliskim Wschodzie. Około 1903 r., z matką i dwiema siostrami, osiedlił się w Nowym Jorku gdzie, aby uzupełnić wykształcenie, zapisał się do Art Students League oraz The Chase School. W 1911 r. przyjął obywatelstwo amerykańskie, natomiast dziewięć lat później wstąpił w związek małżeński z Romolą Campbell[7].

W. T. Benda wykazywał wiele umiejętności artystycznych, był nie tylko ilustratorem, ale i malarzem (zajmował się zarówno malarstwem sztalugowym, jak i freskami), twórcą masek, projektantem i rzeźbiarzem, a także publicysta i pisarzem oraz aktorem.

Lata 1880 – 1940, to okres tzw. „Złotej Ery Ilustracji Amerykańskiej”[8]. W czas ten doskonale wpisuje się twórczość W. T. Bendy, zaliczanego obecnie w historii sztuki Stanów Zjednoczonych do czołówki ilustratorów.

Cała historia zaczęła się po przeprowadzce do Nowego Jorku, gdzie od 1906 r. Benda pracował dla American Lithographic Company. Wtedy to redaktor artystyczny „Scribner’s” – Joseph Chapin powierzył artyście zadanie, dzięki któremu mógł pokazać szerszej publiczności swoje prace. Zlecenie, jakie otrzymał stało się przepustką do innych poczytnych czasopism i oficyn wydawniczych. Twórcę okrzyknięto jednym z najbardziej popularnych ilustratorów owych czasów. Jego dzieła zdobiły takie magazyny jak: „Century Magazine”, „Cosmopolitan”, „Life”, „Liberty”, „Scribner’s”, „Redbook”, „Saturday Evening Post”, „Hearst Magazine”, „American”, „Outlook” i wiele, wiele innych.

W jego karierze pojawiały się również liczne zamówienia na dekorowanie książek. Stworzył ilustracje do dzieł Arthura Conana Doyle’a, Rudyarda Kiplinga, Louisa Stevensona, czy Jamesa Curwooda. Z literatury polskiej z jego rycinami ukazał się przekład powieści Zofii Nałkowskiej „Woman”. Prace Bendy wykorzystywane były w kampaniach reklamowych takich firm jak Metropolitan Life, Ivory Soap. Ponadto artysta tworzył propagandowe plakaty, które służyły do rekrutacji, zarówno w Polsce jak i Ameryce, podczas obydwóch wojen światowych. Działalność ta przyniosła Bendzie wielki honor. Za czynne członkowstwo w American Polish Relief Committee Marceliny Sembrich-Kochańskiej i Ignacego J. Paderewskiego, podczas I wojny światowej, został odznaczony Orderem Polonia Restituta[9].

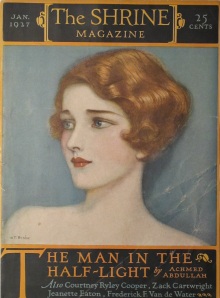

W latach 20. XX w. artysta skierował zainteresowania twórcze w stronę damskiego portretu, wpisując się tym samym w czas kobiet, jaki nastał zarówno w ewoluującym społeczeństwie, jak i sztuce. Panie zdobywały wolność i niezależność, a ilustracja towarzyszyła ich każdemu krokowi. W okresie tym istniał narzucony, specyficzny kanon piękna, którego najsłynniejszym propagatorem był Charles D. Gibson. Ilustrator ów stworzył ideał „American Beauty”, zwany wymiennie „Gibson’s Girls”[10].

Piękne i wymuskane dziewczyny, królowały na okładkach, plakatach i w kampaniach reklamowych. Ich wszechwładza upadła, gdy na scenie plastycznej ukazały się „Benda’s Girls”. Nowy obraz kobiety pełnej egzotyki i tajemniczości, przepełniały cechy charakteru, myśli, marzenia, radości i smutki. Niedoświadczona wcześniej intrygująca głębia wizerunku. „Kiedy wyobrażenia mężczyzn objawiają szorstki realizm, portrety kobiet odsłaniają niezwykły szacunek dla ich piękna i wewnętrznej siły” – pisali o „dziewczynach Bendy” działacze nowojorskiego Illustration House[11]. Teoretycy zwracali uwagę na podkreślane przez artystę cechy fizjonomii, co w całości zmierzało do uwydatnienia „egzotycznej ponętności” portretowanych modelek[12]. Sam Benda wypowiadał się w temacie następująco: „Kobiecy urok to nieuchwytna jakość, to ciężko dostrzegalne niuanse cech i ekspresji, które inspirują do stworzenia ponętnych panien z zadziwiającymi, przelotnymi uśmiechami”[13].

Największy sukces odniósł artysta dokonując wskrzeszenia tradycji tworzenia masek teatralnych. Nazywane „oddychającymi pięknościami” zyskały uznanie i podziw całego świata. Era masek zaczęła się w 1914 r., kiedy to „[…] perspektywa pójścia na maskaradę pchnęła mnie do zrobienia pierwszej maski dla samego siebie… Była zrobiona pospiesznie z kawałków kartonu i papieru, a przedstawiała… groźną twarz demona. Była marna i pełna niedoskonałości, lecz… okazane zainteresowanie dziełem zmotywowało mnie do zrobienia następnych”[14]. Źródeł fascynacji maskami, można dopatrywać się znacznie głębiej. Władysław Teodor dorastał w rodzinie aktorów teatralnych. Wychowywał się przy scenie, wśród kostiumów i licznych rekwizytów. Ponadto, jak sam przyznawał „od wczesnych dni dzieciństwa… drutowałem i kleiłem papiery w kształt zabawek, kukiełek i malutkich miasteczek. Ten wytrwały nawyk robienia rzeczy, przy późniejszej pomocy techniki ze studiów artystycznych, był powodem odkrycia późniejszych uzdolnień do… tworzenie masek”[15].

W 1918 r. odbył się pierwszy pokaz dzieł. Miało to miejsce na Annual Exhibition of The New York Architectural League, gdzie prace spotkały się z entuzjastyczną reakcją kuratorów wystawy i publiczności. W tym samym roku członkowie Comedy Club, odegrali w teatrze, na terenie majątku Charlesa C. Goodricha w Llewellyn Park w Nowym Jorku, „efektowną pantomimę” wspomaganą przez dzieła Bendy[16]. Jednak czas masek nadszedł dopiero w 1920 r., kiedy to Frank Crowninshield zawitał z wizytą w studio artysty, przy Gramercy Park. „[…] od razu zadecydował, że chce mieć je opublikowane w „Vanity Fair”, którego był redaktorem naczelnym. Sfotografował maski, po czym pojawiały się one w kilku kolejnych numerach tego wydawnictwa. Inne magazyny i gazety w Ameryce jak i poza Nią, poszły za tym przykładem” – wspominał artysta[17].

Zaskakujące nowatorstwem ówczesną publiczność dzieła artysty wkroczyły na deski teatrów. Występowały w nich znane, międzynarodowe tancerki – Margaret Severn i Grace Christie, czy solista baletów rosyjskich i Metropolitan Opera – Adolf Bolm[18]. Nagrodzony Noblem amerykański dramatopisarz Eugene O’Neill, także uległ urokowi masek, którego powiodły go do stworzenia sztuk – „Wielki Bóg Brown” oraz „I śmiał się Łazarz”, jak również opublikowania kilku tekstów teoretycznych na ten temat[19]. Ostatecznie zawładnęły filmem. M.in. wykorzystał je, w 1932 r., reżyser Charles Brabin w ekranizacji powieści Saxa Romera „The Mask of Fu Manchu”[20]. Wielkim sukcesem, który przypieczętował władze Bendy w dziedzinie tworzenia masek, była sesja fotograficzna stworzona dla jednego z numerów „Vogue”. Najpopularniejsze modelki owych czasów, ukryte za maskami uwiecznił na fotografiach Edwarda Steichen.

Sława dzieł przyniosła artyście zaproszenie od edycji „Encyklopedii Britannica” z 1929 r., dla której napisał hasło o współczesnych maskach. Ponadto publikował artykuły naukowo – techniczne, które ukazywały się w licznych czasopismach i gazetach. W 1944 r. Benda poważył się spisać i zilustrować książkę „Masks”. Na publikację składały się studia nad własnymi projektami i unikalnymi technikami konstrukcji oraz dekorowania wyrobów. Dodatkowo książka zawierała kilkadziesiąt reprodukcji autorskich dzieł, jak również opisy i wspomnienia ilustrujące dzieje tzw. „Masek Bendy”.

Sposoby wyrabiania dzieł Benda opracowywał zupełnie sam. „Moje obecne metody, to pożądany rezultat dwudziestu lat eksperymentowania”[21]. Działania mechaniczne poprzedzane były długimi studiami natury, analizowaniem i wytężaniem wyobraźni. Dobór tematów, nazywał opętaniem wizjami[22]. Maski tworzone były z pojedynczych pasków papieru, nakładanych na siebie warstwami i sklejanych w odpowiedni sposób.

Po wyrobieniu korpusu, następowała ciężka praca nad dekorowaniem dzieła. Tworzenie masek traktował Benda jak „osobliwy rodzaj rzeźby”[23]. Artysta nie ograniczał się wyłącznie do metodyki tworzenia. Opracowywał teoretyczną stronę zajęcia, jak również argumenty potrzebne do jego nobilitacji. Dowodził znaczenia masek w pantomimach i tańcu. Stworzył własną typografie dzieł, dzieląc je na trzy podstawowe kategorie. Maski w ludzkim typie, nazywane również „ślicznotkami”, maski fantastyczne lub groteskowe oraz komiczne[24]. Artysta stał się niekwestionowanym ekspertem w dziedzinie zapomnianej sztuki. Oprócz publikowania liczne rozprawy, wielokrotnie wyjeżdżał w najróżniejsze zakątki kraju z prelekcjami na temat masek.

Pod koniec życia W. T. Benda stał się rezydentem Fundacji Kościuszkowskiej. Tworzył dla organizacji exlibrisy, grafiki promocyjne i efektowne projekty okładek „Dzienników Bali Fundacji Kościuszkowskiej”[25]. W okresie tym w twórczości Bendy nastąpił powrót do przedstawianych w sposób symboliczny i idealistyczny tematów polskich tj. nokturny, Kraków, czy tajemnicze Tatry. Artysta nie wykorzystywał stricte opatentowanych wyobrażeń. Do końca udoskonalał własną sztukę, m.in. nadając jej nowy element – dekoracyjność. Dzięki takim zabiegom, z zamysłu zwykłe okładki czy druki stały się poszukiwanymi obiektami kolekcjonerskimi. Obecnie Fundacja posiada znaczną kolekcję dzieł Bendy i nadal szczyci się kartą historii zatytułowaną jego imieniem[26].

30 listopada 1948 r. w Newark Public School of Fine and Industrial Art w New Jersey, tuż przed rozpoczęciem kolejnego wystąpienia W. T. Benda zmarł w wyniku ataku serca.

Dorobek artystyczny zacnego twórcy znajduję się głównie w Stanach Zjednoczonych. Wiele dzieł W. T. Bendy należy do prywatnych kolekcjonerów, jak również pozostaje własnością rodziny (córki i wnuków).

Sporą kolekcję posiada Fundacja Kościuszkowska oraz The Polish Museum of America w Chicago[27]. Wiele obrazów utraconych zostało bezpowrotnie w Alliance College Cambridge Springs w Pensylwanii podczas pożaru, który miał miejsce w 1931 r. W Polsce odnaleźć można śladowe egzemplarze twórczości W. T. Bendy. W Poznaniu znajduje się zbiór rysunków, a dwa plakaty należą do Centralnej Biblioteki Wojskowej w Warszawie[28].

Władysław Teodor Benda zaliczany do czołówki amerykańskich artystów, zajmuje poczytne miejsce w sztuce; obok takich postaci jak: Charles Dana Gibson, Coles Phillips, Nell Brinkley, czy Russell Patterson; a jego sława odbija się echem po dzień dzisiejszy.

[1] Niniejszy tekst stanowi podsumowanie dotychczasowych badań nad życiem i twórczością W. T. Bendy, czynionych przez autorkę w zamiarze stworzenia, jako pracy doktoranckiej, monografii artysty.

[2] M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca masek teatralnych, „Pamiętnik Teatralny”, R: LV, z. 1-2 (221-222), Warszawa 2007, s. 70. Dziękuję autorce tekstu za udostępnienie maszynopisu oraz niezwykle cenne wskazówki i konsultacje.

[3] Tamże, s. 70.

[4] Określenia cytowane za: J. Szczublewski, Żywot Modrzejewskiej, Warszawa 1975, s. 599.

[5] H. Modrzejewska, Wspomnienia i wrażenia, tłum. M. Promiński, Kraków 1957, s. 561.

[6] Za: M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca…, dz.cyt., s. 70-71.

[7] Tamże, s. 71.

[8] Datacja przyjęta za: M. B. Pohlad, Introduction, [w:] Selected drawings of W. T. Benda, St. Louis 2006.

[9] M. Szydłowska, Świat wyobraźni Władysława Teodora Bendy, http://dziennik.com/www/dziennik/kult/archiwum/01-06-06/pp-01-06-01.html, (dostęp: 15.04.2007).

[10] The Marketing of the American Beauty, The Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/beauties/beauties-kelly.html, (dostęp: 17.02.2008).

[11] W. T. Benda, Exotic drawings & theatrical masks, ed. W. Reed, J. Pratzon, F. Taraba, „The Illustration Collector”, 1993:30, p. five, (tłum. A.B.Rudek).

[12] Tamże.

[13] Tamże.

[14] W. T. Benda, Masks, New York 1944, p. 51, (tłum. A.B.Rudek).

[15] Tamże.

[16] Tamże, p.54.

[17] Tamże.

[18] George Estman House w Nowym Jorku posiada w zbiorach zdjęcia wykonane przez Nicolasa Muray, przedstawiające Margaret Severn w maskach Bendy.

[19] Szerzej o tym: M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca…, dz.cyt., s. 83.

[20] L. Knapp, The Mask, 26 grudnia 2006, http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/Mask.htm, (dostęp: 13.12.2007).

[21] W. T. Benda, Masks, dz.cyt., p. 31.

[22] Tamże, p. 21.

[23] Tamże, p. 20.

[24] Podział masek przyjęty za: W. Reed, J. Pratzon, F. Taraba, [w:] W. T. Benda…, dz.cyt., p. eight.

[25] www.kosciuszkofoundation.org/News_Benda.html (dostęp: 12.06.2007).

[26] W kwietniu 2007 r., w holu Fundacji można było oglądać wystawę poświęconą artyście. Ekspozycja, stworzona przy współpracy z żyjącymi członkami najbliższej rodziny Bendy prezentowała zarówno maski, okładki czasopism, jak i obrazy.

[27] E-mail od M. Kot (The Polish Museum of America, Chicago) do A. Rudek, Chicago 30 stycznia 2008, korespondencja w posiadaniu autorki.

[28] E-mail od G. Kubiak (Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu) do A. Rudek, 25 stycznia 2008, korespondencja w posiadaniu autorki; M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca..., dz. cyt., s. 72.

______________________________

ENGLISH VERSION

Wladyslaw Theodor Benda, ‘The Archives of Polish Emigration’, Torun, issue 1, vol. 10/2009, pp. 168-172.

Talented. Inventive. Aware of tradition and roots. Work Titan. A Child of Its Time. An illustrator, a painter, a world- famous mask maker. Wladyslaw Theodor Benda, an American of Polish descent, one of the most prominent artists in the Unites States.[1]

His father, Simon Benda, a pianist and composer educated in Vienna, came from Cracow. He was a half- brother of the theatre actress Helena Modrzejewska. He married Xsawera Sikorska, a merchant’s daughter from Poznan, with whom he had three children. The eldest son, Wladyslaw Theodor, was born in 1873 in Poznan. Although Simon undertook different jobs, working as a music teacher, a theatre bandmaster and a piano factory representative, Benda’s family lived in poverty. Constant moving from one city to another (Cracow, Poznan, Vienna, Tarnow), was not getting their financial situation better.

Wladyslaw began his art study at the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts, thanks to the help of his grandmother and aunt. He studied under Wladyslaw Luszczkiewicz, Izydor Jablonski, and Florian S. Cynk.[2] Since 1894 he had stayed in Vienna, where he continued his studies at the Heinrich Strehblow School of Fine Arts.[3]

In 1898, invited by his sister, Simon Benda’s family went to the United States. At that time Modrzejewska was on the threshold of a great and well – planned career. She had already owned a large estate in California, and had widespread and significant connections. The aunt facilitated her nephew entering into the art world, by commissioning him to design the scenery and to prepare stage costumes to William Shakespeare’s ‘Antony and Cleopatra.’ The premiere took place on September 19, 1898, at the Baldwin Theatre in San Francisco. The play was proclaimed a ‘historic event’ in the city history, and the costumes gained the name ‘marvellous.’[4] Modrzejewska, playing the part of Cleopatra, achieved great success. ‘I am glad to say that this time, as before, Shakespeare proved a good friend to me. The play was a success…’[5]– the actress wrote in her memoires.

The artist’s father died in 1899. He himself had moved to Los Angeles, and then to San Francisco, where he studied at the Hopkins Institute of Art.[6] He also traveled around Europe and the Middle East. About 1903, he settled in New York with his mother and two sisters, where he joined the Art Students League and the Chase School, in order to complete his education. He became an American citizen in 1911, whereas nine years later he married Romola Campbell.[7]

W.T. Benda revealed many artistic skills, not only was he an illustrator, but also a painter (he dealt with both easel painting and fresco), a mask maker, a designer, a sculptor, as well as a journalist, a writer and an actor.

Years 1880-1940 fall to the so-called ‘Golden Age of American Illustration.’[8] W.T. Benda’s works perfectly suit that time, and the artist himself is currently included in the lead of illustrators in the United States’ art history.

The whole story began after Benda had moved to New York, where he had worked for the American Lithographic Company since 1906. It was then, that the art editor of ‘Scribner’s’, Joseph Chapin, entrusted him with a task, thanks to which he could present his works to a wider audience. This commission became his passport to other popular magazines and publishing houses. The artist was acclaimed as one of the most popular illustrators of those times. His works adorned such magazines as ‘Century Magazine’, ‘Cosmopolitan’, ‘Life’, ‘Liberty’, ‘Scribner’s’, ‘Redbook’, ‘Saturday Evening Post’, ‘Hearst Magazine’, ‘American’, ‘Outlook’, and many others.

During his career he also received many commissions for books decoration. He illustrated works of Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Louis Stevenson and James Curwood. As for the Polish literature, the translation of Zofia Nalkowska’s novel Woman was published with his drawings. Benda’s works were used in advertising campaigns, such as Metropolitan Life and Ivory Soap. Moreover, the artist had created propaganda posters, which served as a recruitment tool, both in Poland and America, during the two World Wars. The above action brought Benda a great honour. For his active membership in the American Polish Relief Committee of Marcelina Sembrich-Kochanska and Ignacy J. Paderewski, during the First World War, he was decorated with ‘Polonia Restituta Order.’[9]

In 1920s the artist turned his creative interests to female portrait, adjusting himself to women’s time, which then came to both evolving society and art. Women were gaining liberty and independence, whereas illustration accompanied their every move. At that time, there existed an imposed, specific beauty canon, of which the most famous propagator was Charles D. Gibson. The illustrator created an ideal of the ‘American Beauty’, alternatively called ‘Gibson’s Girls’.[10] Beautiful and spruce girls, reigned over covers, posters and in advertising campaigns. Their omnipotence declined when ‘Benda’s Girls’ had appeared on the artistic stage. New woman’s image, full of exoticism and mystery, was filled with features of character, thoughts, dreams, joy and sadness. An intriguing depth of image, not experienced before. ‘While Benda’s images of men evince a brusque realism, his portraits of women reveal an exalted regard for their beauty and internal strength’[11] – the activists of the New York Illustration House wrote about ‘Benda’s Girls.’ The theoreticians drew attention to physiognomy features, highlighted by the artist, what, on the whole, aimed at emphasizing the ‘exotic allure’ of portrayed models.[12] Benda himself commented on the subject as follows: ‘Feminine loveliness, its elusive qualities, its hardly discernible nuances of features and expression, will inspire [the artist] to create alluring maidens with mystifying, evanescent smiles.’[13]

The artist attained his greatest success while reviving the tradition of making theatre masks. Called ‘breathing beauties’, they received recognition and admiration of the entire world. The age of masks began in 1914, when ‘[…] going to a masquerade […], furnished the decisive incentive, and I made my first mask. It was hastily constructed of pieces of cardboard and paper and represented […] the grim face of a demon. It was flimsy and full of imperfections, but the impression it created at the dance astonished me […] I set to work improving my mask […].’[14] The sources of mask fascination can be perceived much deeper. Wladyslaw Theodor was growing up in a family of theatre actors. He was brought up near a stage, among costumes and numerous props. What is more as he admitted himself ‘since my early boyhood days […] I have always tinkered, whittled or glued paper into shapes of toys, puppets, and diminutive towns. This persistent habit of making of masks […] would sooner or later suggest the idea of a thing as theatrical as is the mask.’[15] The first exhibition of his works took place in 1918. It was at the Annual Exhibition of The New York Architectural League, where his works were enthusiastically received by the curators and the public. In the same year, the Comedy Club members performed ‘an effective mask-pantomime’ supported with Benda’s works,[16] in the theatre on the estate of Charles C. Goodrich in Llewellyn Park, New York. The age of masks had arrived not until 1920 though. It was when Frank Crowninshield paid the artist a visit in his studio, at Gramercy Park. ‘[…] at once decided to have them published in „Vanity Fair”, of which he was the editor. He had the masks photographed and they appeared in several consecutive issues of that publication. Other magazines and newspapers, in America and abroad, followed his lead.’[17]– reminisced the artist.

The artist’s works entered theatre stages, surprising the then public with their novelty. Famous international dancers, Margaret Severn and Grace Christie, as well as a soloist of Russian ballets and Metropolitan Opera, Adolf Bolm,[18] performed in Benda’s masks. Eugene O’Neill, an American Nobel Prize-winning playwright, also succumbed to the charm of masks, which led him to create the plays ‘The Great God Brown’ and ‘Lazarus Laughed’, and to publish several theoretical texts on the subject.[19] Finally masks seized the movies. Among others, in 1932, they were used by a director Charles Brabin in the film adaptation of Sax Romer’s novel ‘The Mask of Fu Manchu.’[20] A great success, which sealed Benda’s authority in mask- making, came with a photography session made for one of ‘Vogue’ issues. The most popular models of the day, hidden behind the masks, were captured on the photographs taken by Edward Steichen.

The reputation of his works, brought the artist an invitation from ‘Encyclopedia Britannica’ edition from 1929, to wrote an entry on contemporary masks. Moreover, he published scientific- technical articles, which appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers. In 1944 Benda ventured to write and illustrate the book Masks. The publication consisted of a study of his own projects and unique construction and decoration techniques. Additionally, the book incorporated dozens of the author’s work reproductions, as well as descriptions and memories illustrating the age of so- called ‘Benda’s Masks.’

Benda, on his own, formulated the techniques of creating works. ‘My present method, the result of twenty odd years of experimentation, gives the desired results.’[21] Mechanical acts were preceded by extended nature studies, by analyzing and straining the imagination. The selection of subjects he called ‘being possessed by visions.’[22] Masks were made of single stripes of paper, put in layers and glued together in an appropriate way. After having made the body of a mask, a tough decoration work began. Benda treated mask – making as ‘a peculiar kind of sculpture’[23] The artist did not constrain himself only to the methodology of creating. He worked over a theoretical part of the whole activity, but also over arguments to make it noble. He proved the importance of masks in pantomimes and dance. He created his own works typography, dividing them into three basic categories. Human- type masks, called also ‘beauties’, fantastic or grotesque masks, and comic masks.[24] The artist became an unquestionable expert in this forgotten art domain. Apart from publishing numerous papers, he frequently went to various parts of the country with lectures on masks.

At the end of his life W. T. Benda became a resident of The Kosciuszko Foundation, for which he created ex- libris, promotion graphics, and spectacular cover projects of ‘The Kosciuszko Foundation Ball Journals.’[25] At that time, in his creative activity Benda returned to Polish themes, represented in a symbolic and idealistic way, such as nocturnes, Cracow and the mysterious Tatra mountains. The artist did not use strict patented images. To the very end, he improved his own art, among others, by adding a new element, that is decorativeness. Thanks to these endeavors, simple on purpose covers or prints became wanted collection objects. Currently the Foundation owns a remarkable collection of Benda’s works, and still prides itself on a history card wearing his name.[26]

On November 30, 1948, in Newark Public School of Fine and Industrial Art, New Jersey, just before commencing his next presentation, W. T. Benda died of a heart attack.

The artistic achievements of this decent creator are mainly in the United States. Many W.T. Benda’s works belong to private collectors, as well as they constitute his family property (his daughter and grandchildren). The Kosciuszko Foundation and The Polish Museum of America in Chicago[27] also own a vast collection. Many of his paintings were irreversibly forfeited in the fire of the Alliance College Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, in 1931. Trace copies of W. T. Benda’s works can be found in Poland. There is a collection of drawings in Poznan, whereas two posters belong to the Central Military Library in Warsaw.[28]

Wladyslaw Theodor Benda, included in the lead of American artists, holds a respectable place in art, next to such figures as Charles Dana Gibson, Coles Phillips, Nell Brinkley, or Russell Patterson, and his fame has had a widespread impact until these days.

[1] This text constitutes a summary of a hitherto research on life and creative activity of W.T. Benda, carried out by the author with the intention of creating the artist’s monograph in the form of Ph.D. thesis.

[2] M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca masek teatralnych, „Pamiętnik Teatralny”, vol. 55, issues 1-2 (221-222), (Warszawa, 2007) 70. (All translations mine) I thank the author of the quoted text for rendering the manuscript available, as well as for valuable guidelines and consultations.

[3] Ibid. 70.

[4] As cited in: J. Szczublewski, Żywot Modrzejewskiej, (Warszawa, 1975) 599.

[5]H. Modrzejewska, Memories and Impressions of Helena Modjeska, (New York, 1910) 537.

[6]Szydłowska, 70-71.

[7] Szydłowska, 71.

[8] Dates as in: M. B. Pohlad, Introduction, in Selected drawings of W. T. Benda, (St. Louis, 2006)

[9] M. Szydłowska, Świat wyobraźni Władysława Teodora Bendy,

http://dziennik.com/www/dziennik/kult/archiwum/01-06-06/pp-01-06-01.html, April 15, 2007.

[10] The Marketing of the American Beauty, The Library of Congress,

http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/beauties/beauties-kelly.html, February 17,2008.

[11] W. T. Benda, Exotic drawings & theatrical masks, W. Reed, J. Pratzon, F. Taraba, ed. „The Illustration Collector”, (1993:30), 5.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] W. T. Benda, Masks, (New York, 1944) 51.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. 54.

[17] Ibid.

[18] George Estman House in New York is in possession of photographs taken by Nicolas Muray, showing Margaret Severn in Benda’s masks.

[19] More in: M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca…,op.cit., 83.

[20] L. Knapp, The Mask, December 26, 2006, http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/Mask.htm, December 12, 2007.

[21] W. T. Benda, Masks., op.cit., 31.

[22] Ibid. 21.

[23] Ibid. 20.

[24] Masks’ division after: W. Reed, J. Pratzon, F. Taraba, in W. T. Benda…, op.cit., 8.

[25] http://www.kosciuszkofoundation.org/News_Benda.html, June 12, 2007.

[26] In April, 2007, in The Foundation’s hall, there was an exhibition devoted to the artist. The exhibition, created in co-operation with Benda’s closest family members, displayed both masks and magazines’ covers, as well as his paintings.

[27] An e-mail from M. Kot (The Polish Museum of America, Chicago) to A. Rudek, Chicago, January 30, 2008. Correspondence in possession of the author.

[28] An e-mail from G. Kubiak (The National Museum in Poznan) to A. Rudek, January 25, 2008. Correspondence in possession of the author; M. Szydłowska, Władysław Teodor Benda – twórca...,op.cit.,72.

I actually blog likewise and I’m composing something

very close to this excellent blog post, “Władysław Teodor Benda

� Art Continent”. Do you really care in the event I personallyapply a little of your own

points? Many thanks -Adrian

I don’t mind if you will link to my blog :). Let me know when you write your text. I read with pleasure. Best wishes! Ania